HOME COOKING AND MORE

The James Beard Foundation’s 2012 cookbook of the year, Modernist Cuisine: The Art and Science of Cooking, by Nathan Mvhrvold with Chris Young and Maxime Bilet, comprises six volumes and 2,438 pages. Even though its list price of $625 signifies an investment (of book-shelf real estate as well as moolah), it seems reasonable when you consider the prodigious—and invaluable—research and expertise that went into the book’s creation. It changes what every serious cook knows—or thinks he or she knows—and does so in an imaginative, compelling way.

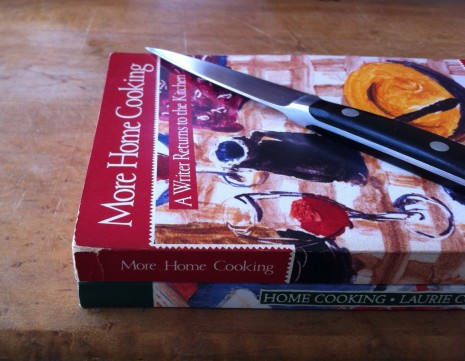

I sure hope it has legs. You know, like the two far more modest books above, Home Cooking (1988) and More Home Cooking (1993), written by Laurie Colwin and just ushered into the Beard Foundation’s Cookbook Hall of Fame.

The books are collections of the columns Laurie wrote for Gourmet from the mid-1980s through the early ’90s. I was fortunate enough to edit many of her monthly essays, which she would mail in, in batches of five or so. I cherished the fact that the person behind the intimate conversational tone and impeccable prose couldn’t spell worth a damn.* Fixing that gave me something to do besides tuck in an occasional comma.

Laurie wrote about the connection between farm and table long before that was on the culinary radar. She wrestled with the evolution of the family dinner in a period when working mothers were desperate for advice. She chronicled kitchen horrors and repulsive dinners, which are not the same thing at all. Like her novels and short-story collections, her food writing was honest, vigorous, and full of good cheer; what saved her work from sentimentality was the steely resolve at the core. She never let anyone off the hook.

Laurie was also among the writers I’ve known who taught me that sometimes the smartest thing an editor can do is not mess with something. Of course, her talent was very rare. A born natural, she had a brilliant, unerring sense of pace, character, tone, and style. She was incapable of burying the lede. And her recipes were almost an afterthought. To my mind, they were a breath of fresh air in a magazine overflowing with careful instruction.

I had first made Laurie’s acquaintance years beforehand, when I worked at the offices of Alfred A. Knopf, her publisher. I was new to New York City and Laurie was a starry young novelist who also happened to be extremely kind, wise, and good-hearted. At some point, she discovered I invited almost everyone I met over for supper. “How else will I make friends?” I explained. Laurie was entranced, and dug her datebook out of her bag. “When can I come?” she asked.

My entertaining was never fancy. I was barely making ends meet, so a company meal generally revolved around a big pot of soup, red beans and rice, a roast chicken, or some concoction of staples I’d brought back from my latest trip to Savannah—back then, ingredients like okra and collards were hard to find in the city.

I think I fed Laurie a gumbo. I recall being amazed at how exotic she thought it was, and happy about how good it tasted. We talked about beautiful old plates, the importance of table manners, and under-rated girl groups like the Velvelettes. A couple of days later, a slim package, wrapped in pretty striped paper, was waiting for me at work. “That was a most delicious evening,” Laurie had scrawled on the card. “And you deserve a good knife.”

Laurie died, very unexpectedly, of heart failure, in October 1992. She was 48. Her death left an enormous emptiness in the lives of everyone who knew her, either personally or through her books. I think of her almost every time I pick up one of her novels or short-story collections—they’re not only ageless but all still in print—and, of course, that knife, especially if I’m making one of her recipes. Soon it will be time for her tomato pie, with its Cheddary, crumbly crust, and juicy summer beets with pasta and ginger-spiked beet greens.

But all I have time for today are these staggeringly simple nibblies. Although they are known far and wide as Laurie Colwin’s rosemary walnuts, she would be sure to tell you it wasn’t her recipe, that she had simply bought a jar of them at a school fair, and after begging for the recipe, was directed to The Pink Adobe Cookbook, by Rosalea Murphy.

What’s also important is that even though the nuts are terrific with drinks, they also make a satisfying end to a meal in lieu of dessert. Eat them with oranges and coffee, as Laurie suggests, or pour one last glass of wine and put on some Motown. Laurie would be happy that the Velvelettes are still putting on a show.

Rosemary Walnuts

Makes 2 cups

1. Melt 2½ tablespoons unsalted butter with 2 teaspoons dried rosemary (crumbled), 1 teaspoon salt, and ½ teaspoon cayenne.

2. Pour this mixture over 2 cups walnut halves, tossing to coat them.

3. Bake the nuts on a cookie sheet at 350ºF. for 10 minutes.

* In the acknowledgments to More Home Cooking, my name is misspelled. Is that karma or what? Somewhere, Laurie is laughing.

Posted: May 8th, 2012 under cookbooks, cooking, favorite books, Gourmet magazine, people + places, recipes.

Comments

Comment from Marisa

Time May 8, 2012 at 9:21 pm

Thank you so much for this Laurie Colwin story. She was a childhood friend of my mom’s and it’s always been a regret of mine that I didn’t get to meet her. I actually wrote a blog post about her last fall in which I confessed that she’s my imaginary mentor. http://www.foodinjars.com/2011/11/laurie-colwin-and-pear-gingerbread/

Comment from Cynthia A.

Time May 8, 2012 at 11:28 am

I adored Laurie Colwin, and treasure my copies of Home Cooking and More Home Cooking. Thank you for sharing wonderful memories of her as well as the fact that she was an awful speller. Now I feel even closer to her since in my family I am known as the queen of mispellings.