IT’S ROOT BEER SEASON

June 10 was National Black Cow Day, and even though we celebrated in style, I realized I don’t really need a reason to pop the cap off a frosty bottle of root beer. The most sentimental of soft drinks, it reminds me of backyard picnics on a chenille bedspread, Sunday afternoons at a minor league ballpark, cruising a honky-tonk beach strip with the top down. I love the dark, creamy, carbonated herb-flavored elixir perfectly straight, poured over scoops of vanilla, or turned into an icy granita. You can even put all the elements together, then add some Root liqueur for a very grown-up dessert.

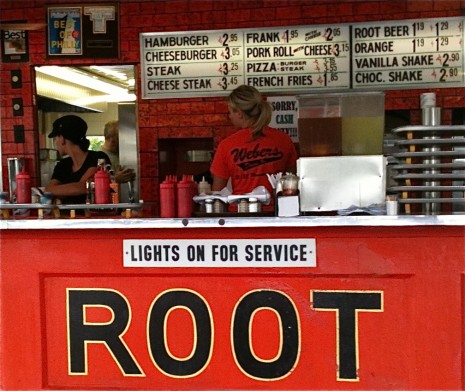

One of my favorite places to get a fix is Weber’s Famous Root Beer* in Pennsauken, New Jersey. I had my first Weber’s root beer float a few years ago, on a roadtrip with Molly O’Neill, the food goddess behind the cook n scribble website. Ever since, a stop at Weber’s is part of any jaunt down to Philadelphia or points south.

Along with two other independently owned Weber’s franchises in New Jersey, the Pennsauken drive-in is an offshoot of a restaurant that opened in Tulsa, Oklahoma, in 1933. Although it retains its circa-1951 amenities—turn on your headlights for car-hop service—it dishes out burgers, pork roll sandwiches, franks, and more without a trace of irony. Weber’s is vintage, not kitsch.

A well-made root beer is rich and mellow, with a decided whang to it; you don’t need a supersized serving to feel satisfied. That said, you can also buy Weber’s freshly made root beer by the gallon jug—a wonderful house present for the weekend host who has everything, especially if you throw in a chic set of spoon-straws, like the ones featured last week at Sally Schneider’s theimprovisedlife.com.

According to The Oxford Companion to American Food and Drink, the sweet soft drink we think of as root beer evolved from English and European low-alcohol “small beers,” carbonated by the fermentation of yeasts. One variation, given tonic properties by spruce or birch bark, was a popular preventative for scurvy, and when the colonists reached North America, they incorporated the similarly flavored sarsaparilla (Smilax ornata) and sassafras (Sassafras albidum) roots used by Cherokee, Choctaw, Iroquois, and other American Indian tribes.

An early mention of so-called “root beer” was in Dr. Chase’s Recipes (1869); the recipe for the spring pick-me-up called for roots of burdock, yellow dock, sarsaparilla, dandelion, and spikenard, along with the oils of spruce and sassafras. The credit for the commercial beverage, however, goes to Philadelphia pharmacist Charles E. Hires, whose nonalcoholic fountain drink as well as a “household extract,” to be used for making root beer at home, were exhibited at the Centennial International Exposition of 1876**. Promoted as a temperance beverage and “hot weather requisite,” it contained “the highest grade of healthful herbs, barks, and berries.” Hires soon began selling bottled root beer and soda fountain syrup.

Today, Hires Root Beer, now owned by the Dr Pepper Snapple Group, is one of the hundreds of root beers available. At one of my neighborhood specialty markets, I counted eight of them—Boylan Bottleworks, Dad’s, Ithaca Soda Co., Maine Root, Natural Brew, Polar Classics, Sprecher, and Virgil’s. Not bad, considering the limited shelf space in Manhattan stores; all too often, the choices are far more limited.

With no standardized recipe, root beer may include ingredients such as vanilla, cinnamon, cloves, licorice root, birch oil, wintergreen, panama bark, yucca extract, hops, juniper berries, star anise, and/or sarsaparilla. You’ll search in vain, though, for sassafras. The FDA banned sassafras root bark in 1960 because of its high content of safrole; tests showed the compound was carcinogenic in rats***. It’s easy enough to dismiss this as a Nanny-State-in-Training regulation, but for centuries, the prevailing folk wisdom has been that sassafras roots dug at the wrong time of year are poisonous—and that’s enough for me.

One ingredient you will see in top-drawer root beers (including Weber’s) is cane sugar. Sugar in every form, of course, is currently Number 1 on the Food Police’s hit list, but many people find cane sugar cleaner on the palate than high-fructose corn syrup. No matter what, check out the ingredients list before falling for just any old-school packaging. Dad’s Old Fashioned Root Beer (“Since 1937”), for instance, has HFCS as its second ingredient, after water. The same is true of today’s Hires and other mass-market brands as well; if your supermarket is lacking in the root beer department, perhaps a summery splurge at realsoda.com is in order. You can also make it at home … or get in the car and ride on down to Weber’s.

*Weber’s Famous Root Beer in Pennsauken is open from around March 1 to the end of October. If you’re heading south on the New Jersey Turnpike, take Exit 4 and follow your car’s increasingly bossy GPS directions to 6019 Lexington Avenue (at Route 38). Weber’s is generally open until 9 or 10 p.m. on summer weekends, but hours do vary; call ahead (856.662.6632) so you won’t be disappointed.

** The Centennial Exposition also saw the introduction of the Remington typewriter, Alexander Graham Bell’s telephone, Heinz ketchup, and kudzu, which must have seemed like a good idea at the time.

*** Happily, the ban doesn’t extend to the powdered dried sassafras leaves known as filé, a seasoning and thickener in gumbos.

Posted: June 12th, 2012 under culinary history, people + places, restaurants, summer.

Comment from Cynthia A.

Time June 12, 2012 at 2:57 pm

I am transported back to summers at my Grammy’s house where she would serve us a special treat of Brown Cows, as she called them. Tall glass, Byrne Dairy ice cream, root beer, a straw and a spoon. Nothing so fancy as a sipper spoon. Great memories.