A PILGRIM’S PROGRESS

Cradling a bourbon in one hand, my father would always remark during our Thanksgiving celebration—in which the turkey played second fiddle to an oyster roast—that southern colonists were throwing cocktail parties by the time the Pilgrims anchored off Cape Cod.

Cradling a bourbon in one hand, my father would always remark during our Thanksgiving celebration—in which the turkey played second fiddle to an oyster roast—that southern colonists were throwing cocktail parties by the time the Pilgrims anchored off Cape Cod.

That must be why milk punch feels so right.

My Thanksgivings here in New York begin in Central Park, at an assembly organized by our friends Thomas Jayne and Rick Ellis. Thomas firmly believes that we are all pilgrims in various ways, and so, for more than 20 years, we’ve gathered to lay a wreath of Indian corn at the base of J. Q. A. Ward’s statue “The Pilgrim” and to read aloud Edward Winslow’s description of the first Thanksgiving feast at Plymouth, Massachusetts, written in 1621.

Today, it was recounted by our friend Alfonso, who just became a citizen this past year. The Mayflower Compact, one of this country’s most important documents, was read by Wendell Garrett, gentleman-scholar and, umpteen years ago, my former boss at Antiques magazine. “I wish our co-op board would adopt something like that,” someone in the crowd muttered.

Stephen Gerth, the rector at the Church of Saint Mary the Virgin, was in charge of the benediction. He prefaced it with the intriguing and comforting notion that perhaps Adam and Eve weren’t expelled from the Garden of Eden because of sin, but because planted within them was the ability and desire to go to someplace new. His benediction was simply four short lines from Pale Fire, written by the 20th-century pilgrim Vladimir Nabokov. “Now I shall spy on beauty as none has / Spied on it yet. Now I shall cry out as / None has cried out. Now I shall try what none / Has tried. Now I shall do what none has done.”

It dovetailed beautifully with the Mayflower Compact, we all agreed. And then it was time for a drink.

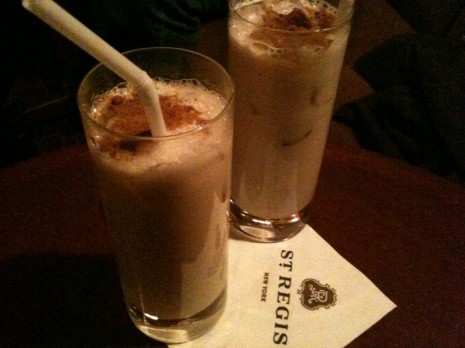

Those of us at the assembly who don’t have a train to catch or dinner to wrangle wander down to the King Cole Bar, in the St. Regis Hotel. We continue the theme of the day with corn-based libations—anything from Diet Coke to a bourbon and branch.

But most of us order a milk punch.

Although lots of people presume milk punch is generically southern, my suspicion that it was a New Orleans libation is confirmed by Rick, a top-drawer food historian. “There are milk punch recipes included in the first cocktail book published in America—How to Mix Drinks, or The Bon Vivant’s Companion,” he says. “It was written by Jerry Thomas and published in New York in 1862.” The first recipe in the book is very similar to recipes one sees today, using brandy and rum instead of bourbon. “One is served hot and the two others are for a rather elaborate preparation called ‘English Milk Punch’—both served cold,” Rick elaborates.

By 1906, a recipe appears in the third edition of The Picayune’s Creole Cook Book. “I don’t have a copy of the first edition [1901],” Rick says longingly. “But I wouldn’t be surprised to see it there.” The recipe, subtitled “Ponche au Lait,” calls for milk, sugar, brandy or whisky, and crushed ice. The sesquicentennial edition of the book includes the same recipe, with an added serving suggestion of a sprinkling of grated nutmeg.

Rick is on a roll. “Mary Land in her Louisiana Cookery—that’s 1954—includes a 30-page chapter devoted to ‘beverages,’ ” he says. “But the only recipe for milk punch is ‘A Milk Punch for the ILL!’—one pint milk, one cup sugar, and two cups sherry. Serve hot.’ ”

Rick and I look at each other. “Honey, I don’t feel well,” we chorus.

Posted: November 25th, 2010 under autumn, culinary history, food, people + places.