OYSTER LOVE

For most people, their first oyster is a rite of passage. M.F.K. Fisher’s was at the Christmas banquet at the southern California boarding school where she was a student. “I swallowed once,” she wrote in The Gastronomical Me, “and felt light and attractive and daring, to know what I had done.” My first wasn’t raw, but an angel on horseback—that is, shucked, wrapped in bacon, and broiled until the bacon is crisp. Angels on horseback were a staple at my mother’s cocktail suppers, and she and my father thought to offer me one at around age eight. Never mind that I was expert at filching them from an unattended baking sheet in the kitchen—that salty, suave, officially sanctioned bite made me feel like a grown-up, part of their social milieu. I soon progressed to roasted oysters and then those on the half shell without a backward look.

My mother saved oyster shells that caught her fancy. One became a grand “alabaster” sink in my dollhouse, but mostly they joined other small, random treasures on the kitchen window sill. Mom might soak okra seeds in them just before planting, or use them to pocket a bit of soil and a tiny bluet, wild violet, or rue anemone. Oyster shells would stand in for salt cellars, both by the stove and on the table.

I picked up my mother’s habit and consequently have a collection of oyster shells that remind me of people and places near and far. Above, at top left, that big ‘un is an Eastern oyster (Crassostrea virginica), which is indigenous to the East and Gulf coasts of North America. Virginicas range from clean-tasting (Wellfleets, from Massachusetts) to beautifully briny (Shooting Point Salts, from the Shooting Point Oyster Company, on the Eastern Shore of Virginia) to sweet and creamy (Apalachicolas, from the Florida Panhandle). Virginicas are also cultivated on the West Coast; one of the most popular is the Totten Inlet virginica, raised by Taylor Shellfish Farms in a bay off Puget Sound. Seafood authority, genius promoter, and longtime friend Jon Rowley introduced me to the Totten, which is sweet, with an alluring mineral finish.

Moving clockwise, you’ll see a virginica from Peconic Bay, Long Island, which is where most of the oysters we eat at home come from these days. The shell that looks like a ruffled party frock is from a mild, rich Pacific oyster (Crassostrea gigas), a species that was brought to the West Coast from Japan in the 1920s; today, it’s commonly cultivated in Europe as well. The little deep-cupped shell below it comes from a Kumamoto (Crassostrea sikamea), originally from Japan and now cultivated successfully in Washington, Oregon, California, and even the cold offshore waters of Mexico. Its diminutive size and sweet-salty balance make it a great “starter” oyster for a novice at a raw bar.

At the bottom is the tiny yet full-flavored Olympia (Ostrea lurida), the only species indigenous to the West Coast. And the round, aptly named European Flat (Ostrea edulis), the famed oyster of Belon, Marennes, and Colchester, has a robust mineral aftertaste that you either adore or equate to french-kissing the bottom of a boat. Overfishing, the parasite Bonamia, and the current passion for smaller, milder oysters have caused edulis to virtually disappear in Europe, but all is not lost. In North America, it’s cultivated on both the East and West coasts, with place names that incorporate the word flat. (For additional info about oysters, as well as why they really are best in the “R” months, take a look at my “Jane Says” column at TakePart.com from a few months back.)

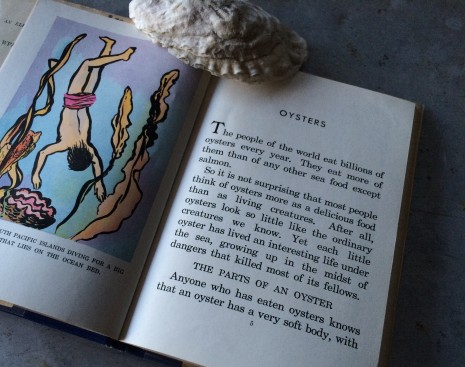

My parents were true educators at heart, and their library included Oysters, a slim hardback prepared by workers in the Writers’ Program of the Work Projects Administration in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, and published in 1941. I cannot tell you how many times I pored over its pages, with their charming illustrations and captions (“The oyster crab, drawn very much larger than it is in real life”). It was my favorite, along with Orchards in All Seasons, in a series of science books for third and fourth graders that also included Life in an Ant Hill, Romance of Rubber, The Story of Bees, and 20-odd other titles.

Not that Sam and I really need an excuse to eat oysters, but it seems only natural to indulge on Valentine’s Day. We’ll be spending it in Orient, a small coastal community way out on the North Fork of Long Island. The English who settled the area around 1661 knew it as Oysterponds.

So our favorite bivalve will be on the menu chez Lear. We might romp through a few dozen raw, on the half shell, or choose instead my father’s Sweetheart Oysters, always a great favorite. Or, if we’re in the mood for some retro chic, angels on horseback. No matter what, I’m on the prowl for some pretty shells. I have a couple for salt cellars, but the window sill—it looks empty.

Posted: February 10th, 2015 under food, oysters, people + places.