There are about as many versions of chowder as there are cooks who make it, which is perfectly reasonable when you think about it. Like vegetable soup or gumbo, it’s more a product of circumstance and soulful interpretation than an actual recipe.

I myself was raised on a brothy Hatteras clam chowder, which tastes of the ocean, not of cream or tomatoes, but this dratted weather (we’re eagerly awaiting an alleged “warming trend”) calls for something more substantial and nourishing. You might think that living in New York City would incline me to Manhattan chowder: Bright with tomatoes, it has a clean, piquant flavor that’s very appealing. The food writer John Thorne, who grew up on Down East cooking, suspects Manhattan clam chowder is a New World variation of the very similar Neapolitan zuppa de vongole. In a masterful essay on chowder in Serious Pig: An American Cook in Search of His Roots (you can pick up a signed copy at John’s Simple Cooking website), he also noted that some Yankee cooks were putting tomatoes in their chowders from the middle of the 19th century, when tomatoes, whether fresh or canned, provided novelty, much like chiles do today.

“However, if there was one place left mostly untouched by the great tomato craze it was Down East Maine,” John wrote. “In 1855, a decade after the rest of the country was consuming them as if there were no tomorrow, the Maine Farmer was reporting that folks here were just beginning to acknowledge that they might be edible.”

Milk is more of a newcomer to chowder than the tomato, he added, “but it enhanced rather than changed what was an established taste …. The very word ‘chowder’ is simply and unreflectively evocative of a liquid elixir built on a foundation of salt pork, onion, and potato, aswim with seafood in a broth tempered with milk and thickened with a handful of crackers. And there’s no reason in the world to want that to change.”

I couldn’t agree more. And hewing to the New England tradition certainly simplifies a shopping list. Even though salt pork is the quintessential Down East chowder ingredient, I’ve given up finding a convenient source for good-quality stuff in New York. Yes, I know I can actually make salt pork from scratch, but until I get around to it, I’ll automatically substitute bacon. In this household, we’re never short of that, let alone potatoes and onions. I straddled the milk/cream debate by buying a pint of half-and-half at the corner store; it provides richness without slip-sliding into gloppiness. In a perfect world, I would have foraged farther afield for common crackers, but it was so raw and cold, the box of oyster crackers in the pantry would do nicely.

More on the seasoning meat: The richness of salt pork or the smokiness of bacon are marvelous building blocks in a chowder, but given great clams and potatoes, you can certainly live without them.

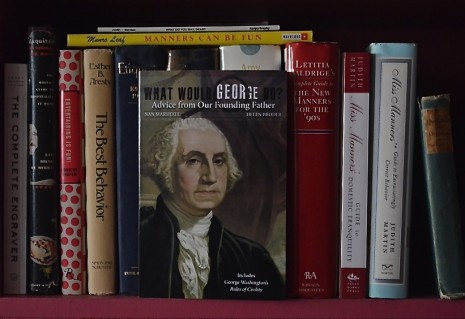

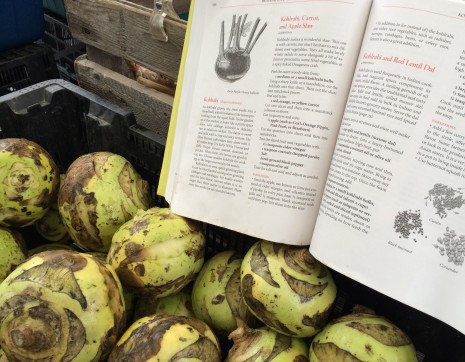

Now, about the clams: All Atlantic hard-shell clams are all the same bivalve species—Mercenaria mercenaria. Also called quahogs (pronounced “KO–hogs”), they are distinguished by size. The beauts you see in the above photo are so-called middle neck clams (seven to nine per pound) from the Eastern Shore of Virginia—specifically, from the pristine waters of Quinby Inlet, on the north end of Hog Island. A few years back, I watched them being harvested by Tom Gallivan, who, in addition to running Shooting Point Oyster Company with his wife, Ann, works with JC Walker Brothers (est. 1889) and HM Terry Company (est. 1903) to sustainably cultivate millions of clams and oysters for raw bars and restaurants nationwide. It has been too long since I last visited Tom’s part of Virginia, but Pisacane, our neighborhood’s seafood market for 50-plus years, had plenty of sparkling-fresh little necks on hand. I was in business.

About the potatoes: Avoid russet (baking) potatoes, which dissolve in a chowder, and new potatoes, which as John pointed out in Serious Pig, “refuse to interact with a chowder at all.” Instead you need a plain all-purpose potato such as Kennebec, Superior, or even Yukon Gold. Don’t peel the potatoes ahead of time for efficiency’s sake; you want all their lovely starch to thicken the chowder instead of the cold water you’ve put them in to prevent discoloration.

Although I’m usually a huge proponent of cutting potatoes (or any other ingredient) into same-sized pieces so they cook evenly, that is not the case when it comes to chowder. Instead, I’ve learned to cut traditional “thick-thin” slices by standing each peeled spud on end and using a paring knife to whittle off bite-size pieces around the outside so that each piece has a thin edge and a thick edge. “The thin edge cooks off and helps thicken the chowder,” explained food historian Sandy Oliver in Maine Home Cooking. Potatoes cut thick-thin are an essential but too little known trick, John Thorne wrote. “Bits of the edge break away to meld into the liquid as the potatoes simmer in the pot, creating a uniquely creamy body.” And how. My next batch of leek and potato soup is going to be all the better for it.

About the crackers: “You can improve any chowder with a trick my mother taught me,” wrote John. “Crumble a few common crackers in your fist or under a rolling pin and sauté these in the fat with the onion, before pouring in the broth. Then split and toast a few more—or, even better, fry them until golden in melted butter in a small skillet—to float on top of the chowder at the point of serving.” My new favorite croutons.

And there you have it: an alluring balance of spare simplicity and warming good cheer. I could live on this chowder for the entire month of March.

New England Clam Chowder

With thanks to Serious Pig, by John Thorne with Matt Lewis Thorne (HarperCollins, 1996), Maine Home Cooking, by Sandra L. Oliver (Down East, 2012), and The Gourmet Cookbook (Houghton Mifflin, 2004)

Makes about 5 cups

3 dozen small hard-shelled clams (less than 2 inches wide), such as little necks or middle necks, scrubbed well

1½ cups cold water

2 or 3 medium potatoes such as Kennebec, Yukon Gold, or “all-purpose” potatoes, plus another 1 or 2 for the pot

Unsalted butter

2 slices bacon, chopped (optional)

Common crackers, split horizontally in half, or oyster crackers

1 small onion, chopped

1 cup half-and-half

Coarse salt and freshly ground pepper

1. Put the clams and cold water in a 4-quart pot and bring to a boil over moderately high heat. Cover and steam the clams until they open, 5 to 10 minutes, checking frequently after 5 minutes and transferring them to a bowl as they open. Discard any clams that have not opened.

2. Pour the broth though a fine-mesh sieve into another bowl, leaving any grit in pot. When the clams are cool enough to handle, remove them from their shells and coarsely chop. Add any liquid from the shells and clams to the bowl of broth.

3. Peel the potatoes and cut into “thick-thin” wedges (see above note on potatoes) or, if you choose, irregular cubes roughly the size of the chopped clams. Meanwhile, melt 2 tablespoons butter in a large saucepan over moderate heat. Add the bacon, if using, and cook, stirring occasionally, until golden, about 4 minutes. Crumble a handful of crackers into the pan, add the onion, and cook, stirring, until the crackers start to disintegrate and the onion is softened, about 5 minutes.

4. Stir in the potatoes and strained broth. Bring to a simmer, and simmer, covered, until the potatoes are very tender and just barely holding their shape, about 10 minutes or so; the timing depends on the type of potato and the size of the pieces. Stir in the clams and half-and-half; season with salt and pepper. Cook (do not let boil) until heated through, about 1 minute. Let the chowder sit on the back burner for an hour before gently reheating until it’s steaming hot (again, don’t let it boil). You can also make the chowder earlier in the day and let it cool completely before refrigerating it.

4. While reheating the chowder, melt a generous pat of butter in a small skillet over moderate heat and fry a generous amount of crackers. To serve, float the crackers and (gilding the lily here) a thin pat of butter on top of each serving.