CULINARY EPHEMERA: YOU NEVER KNOW WHERE A PAPER TRAIL WILL LEAD YOU

When William Woys Weaver learned that his Culinary Ephemera: An Illustrated History had taken top honors for culinary history at the IACP (International Association of Culinary Professionals) cookbook awards, presented last week in Austin, Texas, he responded in characteristic, generous fashion. He fired off an e-mail thank-you to everyone in his orbit.

“Dear Friends,” he wrote. “I have learned this evening that my book Culinary Ephemera took first place in the IACP cookbook awards for the category ‘Culinary History.’ IACP has done much to elevate this branch of food studies and I am deeply honored to take the gold since this will give other struggling food scholars the kind of recognition they deserve in a field that has only just recently come into its own. I had a little prosecco to celebrate the award and to remind myself how lucky I am to have all of you as my friends. Yes, YOU!!! Where would I be without my family of friends?”

And where would we be without Will Weaver?

Back in the late 1990s, when I first stumbled across Will’s Heirloom Vegetable Gardening—an instant classic—I knew his voice belonged in the pages of Gourmet. Years of happy collaboration followed. A food historian and master gardener who maintains around 4,500 varieties of vegetables, flowers, and herbs in his Roughwood Seed Collection, in Devon, Pennsylvania, he was game for writing about anything. Tomatoes. Potatoes. Squash. Melons. You name it: We asked, he responded with alacrity and panache.

Will nurtures people like his beloved dahlias. When the staff at the magazine was pole-axed, one after another, by a particularly vicious cold (“You’ve been sick for weeks,” he said to me, anxious and aghast. “How long have you had that cough?”), he immediately posted a care package of herbs, with carefully detailed notes for a tisane. At the time, he was deep in the weeds, translating Sauer’s Herbal Cures: America’s First Book of Botanic Healing, written in German by a Colonial American apothecary, and we took him at his word. Mugs of the steaming hot liquid were carefully passed around, and “… what in God’s name was in that?” we all said a day or so later. He had coaxed us back into bloom.

For the past few years, Will poured much of his prodigious energy into Culinary Ephemera, which is based on his collection of almost 50,000 almanacs, calendars, handbills, menus, match covers, trade cards, product pamphlets, packaging, valentines, and much more. I came across a quote from him I’d scribbled down in a kitchen notebook ages ago. “Old cookbooks are important for interpreting culture,” he had told me, “but they’re not enough. Just like archaeology needs many different kinds of artifacts, so does food history.”

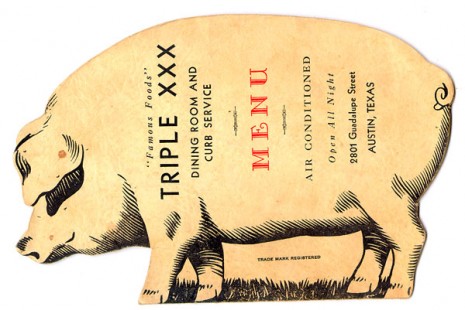

Will and I share a fascination for menus both haute and humble. I really like the one up above, partly because of the amazing graphic quality of the die-cut, and partly because of its Austin provenance—fitting, in light of where the IACP conference was held this year. The menu, published in 1939 by the Triple XXX Pig Stand, documents a regional restaurant that first opened in Dallas in 1921 and claimed to be the first drive-in restaurant in the United States. “At drive-ins, Americans could sit in their cars and eat and enjoy the scenery at the same time, albeit in a less glamorous way than was possible on the railroads,” Will wrote. “…. This ordinary experience became the new standard, the new chic.”

I am also extremely fond of postcards, and I shamelessly wallowed in Will’s chapter on collecting them—a pastime called deltiology. By 1900, when the “real photo postcard” began to take hold, food, food processing, people harvesting, and restaurants had become topics of interest. “Food postcards create their own reality, apart from that which is depicted,” said Will yesterday. “They create expectation.”

Most of these early American postcards were, in fact, printed in Germany, where color lithography was invented. The arresting image above, depicting a long-vanished renowned Atlantic City hotel bordered by lobsters is a great example. The lobster, of course, is an icon for a typical New England “shore dinner,” which rapidly captured the imagination and appetites of resort-goers all along the Eastern Seaboard and as far inland as Philadelphia and Washington.

You’ll also find the exact same lobster border wrapped around a view of Rumeli Hisari fortress, on the Bosporus. In his charming, evocative Constantinople Old and New (1915), Harrison Griswold Dwight, who grew up there, noted that the local boatmen who ferried tourists from village to village eked out their incomes by fishing. “We are famous for our lobsters at Roumeli Hissar,” he added.

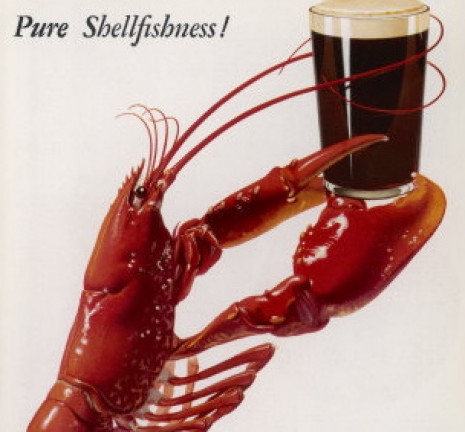

All of these fabulous lobsters lead me to include the most recent addition to my virtual ephemera collection, from an advertising poster that reads, “There’s nothing like a Guinness with Lobster.” I had to crop the hell out of the image to get it to fit in this space, so it’s worth clicking here to get the full effect (note the beautiful typeface).

I also found myself trying to wrap my taste buds, so to speak, around the concept. It had never occurred to me to drink a dry Irish stout with lobster. I had to research this, obviously, and am happy to report that it is delicious.

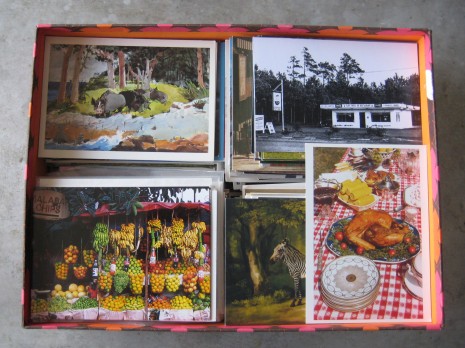

The fact that e-phemera isn’t nearly as satisfying as actual paper is offset somewhat by the fact that it doesn’t take up any room. Like postcards. I’ve collected them for years. They are roughly organized into categories, but my archiving technique can best be described as iffy.

As soon as I opened this box devoted to culinary subjects, I saw some favorites. At top left, there is a very nice Winslow Homer 1901 watercolor called Bermuda Settlers. You may think it belongs in the postcard box labeled “Art,” but relax—there is a dupe there, and the subject matter, wild boar, is perfectly valid here as well. Below it is a souvenir from a trip to southern India; every time I look at it, I’m reminded of the extraordinary meals I had there.

Now, at top right, there is what Will would call a vignette of life as it actually was: Flip’s Drive-In Restaurant, Wilmington, North Carolina, circa 1957. Looking at the photo, I conjure my own reality: My parents walking through the door. My mother would have worn a shirtwaist dress, my father, crumpled khakis and a seersucker jacket. Even though there was curb service, they would have eaten their barbecue sandwiches and fried shrimp inside, where there was a booster seat waiting for me. I still go to Flip’s on occasion. There are far better places for barbecue in that part of the world, but I don’t care. I was too young to remember, but it’s where I ate my first french fry, my first bite of pulled pork.

The postcard at bottom right is of a photograph taken in Tennessee circa 1983–86 by the great William Eggleston. He acquired his first camera, a Canon rangefinder, in 1957, so I like that juxtaposition with Flip’s. The fact that color photography is considered a museum-worthy art form today is one of Mr. Eggleston’s many contributions to the field.

That zebra peeking out from behind the gingham tablecloth has nothing whatsoever to do with food, and I’m not quite sure why that postcard is there. It’s of a George Stubbs painting of 1762–63 that hangs at the Yale Center for British Art in New Haven, Connecticut. Paul Mellon bought the painting, shown amid a jumble of furniture and household goods, at auction at Harrods.

Harrods! The Food Hall. Imagine one of those fancy seagrass hampers, stocked with delectables and a nice bottle of fizz, plunked down in the Eggleston still life. The zebra stays.

Posted: June 7th, 2011 under culinary history, favorite books, food, Gourmet magazine, obsession, people + places.

Comment from K

Time June 8, 2011 at 5:39 am

What a LOVELY piece today, Hane. XOXO–K.