LESSONS, CAROLS, AND GINGERBREAD WITH STARS

A rich and rewarding life doesn’t just happen. You need to surround yourself with interesting people, have a sense of occasion, and know how to make your own fun. My schooling in this began when I was very young.

One mentor I always think of this time of year is Aunt Eloise—in truth, a longtime friend of my mother’s—who sent the most exotic, imaginative presents in the world. One year, the rich, sweet bread called panettone arrived, packed in a bright red and gold box. It had come all the way from Italy, and even after every crumb was eaten, the glamorous box occupied a place of honor on the sideboard. Once she sent a set of chopsticks, which upset family discipline at the dining table for a solid week. Another time, a box of serapes arrived, and then there was the year my brother, Bart, received Indian moccasins, and I received a Cheyenne buckskin dress with fringe, a gift so overwhelming I burst into tears.

When Aunt Eloise was not off adventuring, she would visit us during the holidays. She always arrived in an immaculately maintained Buick, and she insisted on carrying her own suitcase into our wide hall, setting it down with a thump and a little sigh. (“Always travel light, darling,” she counseled, years before I ever went anywhere. “You might have to move fast.” Today, it occurs to me that I have no idea what her husband did for a living.)

Bart and I couldn’t wait to present ourselves before Aunt Eloise because we knew exactly what would happen. She would shake her head in amazement at how much we had grown and hug us thoroughly before rummaging through a capacious alligator handbag. “Oh, they are here somewhere,” she would mutter to herself, before triumphantly producing two chocolate bars, wrapped in thin gold foil and glossy paper. To this day, the scent of a chocolate bar is inextricably bound up with the thrill of arrival in my mind. I’m not a chocolate person by any means, but I really, really love finding one on my pillow in a hotel.

We had to open the chocolate bars very carefully, because Aunt Eloise always wanted the foil back. Like my parents, she had grown up during the Depression, and never wasted a thing. She would smooth the sheets and look mysterious. We knew what was up, and stayed close, so as not to miss anything.

The days before Christmas were filled with tree cutting and decoration, setting up the crèche, which had an expanded cast (my father trolled thrift shops and pawn shops looking, in particular, for Baby Jesuses—he couldn’t bear the thought of them being adrift), and frantic gift wrapping, often in paper that was soft from reuse. I would, under great duress, practice carols under Mom’s energetic direction. “O for the weengs, the weengs of a dove,” I would sing, and anyone within earshot would slip, very quietly, as far away as possible.

The annual greens-gathering expedition—magnolia, pine, holly, box, and spooky mistletoe—was made easy by one of Aunt E.’s gifts to my parents: two machetes. None of the adults, taking turns sipping from a sterling flask, had any qualms about teaching me how to use one. “You’ll do,” said Aunt Eloise. “Do you know how to shoot yet?”

And then, of course, there was the gingerbread. Dark, moist, and spicy, it was Aunt E.’s specialty. That year, she turned to face my brother and me in the kitchen. “I have always made gingerbread for you,” she said, removing her apron and hitching it up, neat and workmanlike, around me. “Now, it’s your turn.” She switched on the oven and then got comfortable at the kitchen table. Mom made cups of tea for them both and buttered the pan.

Bart stirred the flour, baking soda, and spices together. Wielding a machete had given me the confidence to plug in the Sunbeam and to cream the butter and dark brown sugar, then beat in the eggs and cane syrup—preferred by all in our house to molasses. I stopped, startled, when the mixture looked curdled, but Aunt Eloise peered into the bowl and said, “Oh, it’s fine! Just keep going and see what happens.”

After beating in the flour mixture and a little hot water, everything miraculously came together. After my mother helped me pour the batter into the pan, she tucked it into the hot oven.

By the time the dishes were done, so was the gingerbread. Aunt Eloise patted several pockets—she had a magician’s knack for misdirection—before unerringly settling on the right one, then fished out an envelope full of small gold stars, cut out of foil. They smelled, very faintly, of chocolate, as Bart and I pressed them into the warm cake.

I don’t have Aunt Eloise’s recipe, but this is a close approximation. It’s based on the Tropical Gingerbread (minus the canned coconut) in Charleston Receipts—a standard reference for both Aunt E. and my mother—and the Old-Fashioned Gingerbread in the big yellow Gourmet Cookbook.

You could dress it up with a glaze made from lemon juice and confectioners sugar, or with billows of whipped cream flavored with a little bourbon. Both options are absolutely delicious.

But nothing is prettier than gold stars, glimmering in candlelight. I’ve used edible gold leaf instead of foil, but the problem with being so rarified is that you don’t get to slowly peel off the gold stars and make Christmas wishes with them.

CHRISTMAS GINGERBREAD

2 cups all-purpose flour

1 teaspoon baking soda

1½ teaspoons ground ginger

1 teaspoon ground cinnamon

¼ teaspoon cloves or allspice

½ teaspoon salt

1 stick unsalted butter, room temperature

¾ cup firmly packed dark brown sugar

2 large eggs

½ cup pure ribbon cane syrup* or molasses (not robust or blackstrap)

2/3 cup hot water

Preheat the oven to 350° and butter a 9-inch square baking pan. In one bowl, stir together the flour, baking soda, spices, and salt. In another bowl with an electric mixer beat together the butter and brown sugar at medium-high speed until nice and fluffy. I prefer dark brown sugar because it makes the top of the cake slightly crunchy, but light brown sugar is perfectly fine; it will just result in a softer crust.

Beat in the eggs, one at a time, then beat in the cane syrup or molasses. At this point, the batter might look curdled, but, as Aunt Eloise would tell you, don’t worry about it. Reduce the mixer speed to low and beat in the flour mixture, then the water. Continue to beat until the batter is smooth, a minute or so.

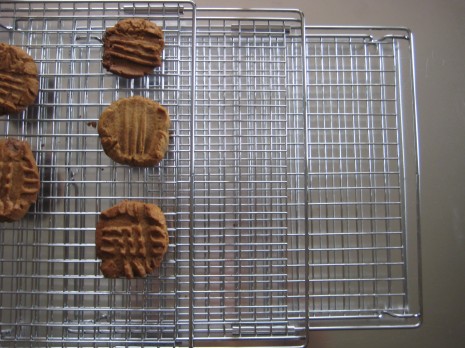

Pour the batter into the pan and bake in the middle of the oven until a wooden skewer inserted in the center of the gingerbread comes out perfectly clean, around 35 minutes. Cool on a wire rack.

* The syrup made from ribbon cane has a little whang to it, like all types of molasses, but it’s lighter and sweeter. Not only is it a versatile baking ingredient, it makes the ultimate condiment for pancakes, waffles, or hot biscuits. Cane syrup is a supermarket item south of the Mason-Dixon; one tried-and-true mail-order source is Steen’s Syrup, from Louisiana.

Posted: December 22nd, 2010 under Christmas, cooking, food, people + places, winter.

Comments: none