MANDARIN-FENNEL SALAD

Salad in winter is a tricky proposition. Tender, young greenhouse lettuces are all well and good, but we all know that most other salad swear-bys—tomatoes are an obvious example—are disappointing out of season.

But more importantly, this type of salad doesn’t suit the heartier, richer food we crave this time of year. A plateful of nicely dressed butterhead lettuces that arrives after braised short ribs, say, or polenta and sausage sauce seems tacked on and curiously unsatisfying. People tend to pick at it and wonder what’s for dessert, rather than appreciate the punctuation, so to speak, and feel revitalized.

To provide the sort of clean, bracing counterpoint that’s called for, a winter salad needs drama and edginess. Assertive greens such as watercress, arugula, endive, or springy, spiky frisée will get you going in the right direction, and slivers of sweet, earthy fresh celery root and/or tangy green apple will help matters along.

A few weeks ago, when I mentioned we planned to follow a fettuccine Alfredo blow-out with a satsuma and fennel combination—one of our favorite winter salads—several people wanted the recipe. It is nothing new, of course, but it is always delicious. What appears below is more of a guideline, really. You can include cress or arugula if you like; substitute green olives for the black, or forgo them altogether. Ruby-red pomegranate seeds would add sparkle and texture, and parsley leaves, an herbal punch.

You’ll see I’m not calling specifically for satsumas—their season just ended—but we’ll all be kept happy with other members in the mandarin citrus family. Tangerines, clementines, and a welter of natural and manmade hybrids are all distinguished by a loose, often bumpy, rind and fruit that easily separates into segments.

Frankly, I find mandarins reason alone to avoid becoming a card-carrying locavore—especially when it comes to the new BMOC, the Dekopon. This burly, much-heralded Japanese mandarin-orange hybrid, characterized by a prominent topknot (see below photo), is now being grown in the San Joaquin Valley under the apt name Sumo (click here for availability). Fruit authority David Karp recently described it as “a perfect blend of sweetness and acidity” with an intense lingering flavor. It is all that and a bag of chips: The fruit segments slip easily out of the ultra-thin membranes and keep their shape on the plate.

Sublime flavor comes in small packages, too. Soon there will be Ojai Pixie tangerines, also from California, and odds are I’ll order a box from Friend’s Ranch or Churchill Orchard. They are little bombs of sunshine.

Mandarin-Fennel Salad

Serves 4

Fennel conjures the Mediterranean—Provence and, of course, Sicily. We live on this salad—bask in it, really—until Spring has truly sprung.

1 large fennel bulb, trimmed of its feathery stalk and some fronds reserved

3 mandarins, peeled

¼ cup brine-cured black olives, if desired

Your favorite best-quality extra-virgin olive oil

Fresh lemon juice

Coarse flaky salt (Maldon adds a wonderful crunch) and freshly ground black pepper

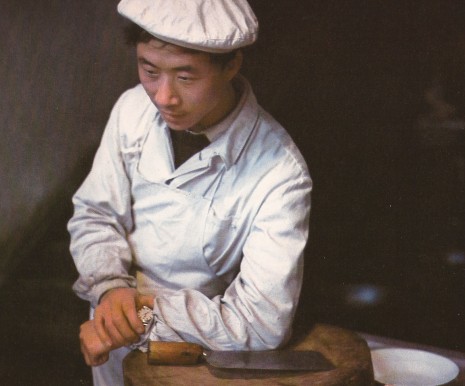

1. Cut the fennel bulb in half lengthwise and discard the tough outer layer or two to expose the cream-colored heart. Then cut the bulb into very thin slices with a handheld slicer (mine is a Benriner, which is friendlier to use than a traditional mandoline) or a very sharp knife. Put them in a salad bowl.

2. Remove the webby pith from the peeled mandarins (children love doing this and are very good at it). Separate the segments and, depending on the thickness and tightness of the membranes that enclose each one, remove those or not; it’s entirely up to you. Cut the fruit in half crosswise and add it, along with the olives, if using, to the salad bowl.

3. Drizzle the salad with olive oil and lemon juice to taste and gently combine. Scatter with salt and a few chopped fennel fronds. Season with a few grinds of pepper. Whoever is at the table will eat every bite.

Posted: February 28th, 2012 under cooking, recipes, winter.

Comments: 1