The first local asparagus stops people in their tracks. They bend over to get a closer look and marvel in the voice they usually reserve for newborns. At the Union Square Greenmarket, where I do a good bit of my shopping, asparagus usually arrives with lilacs and lilies-of-the-valley, a flower to which it is closely related. This past Saturday was no exception: It was impossible not to splurge on spring.

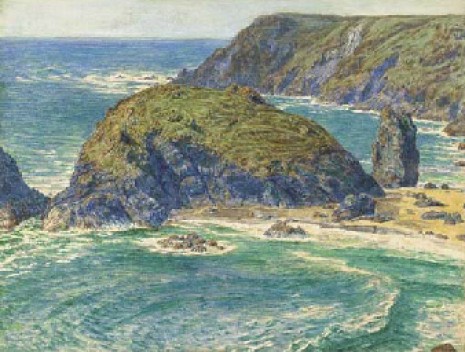

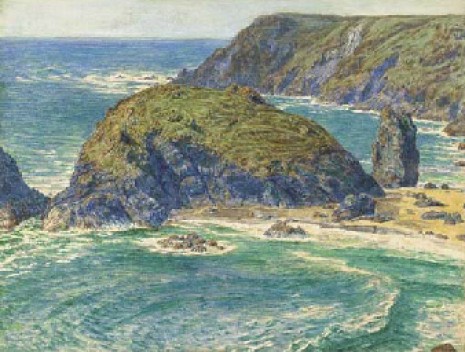

We’re all used to seeing fat bundles of asparagus in the rich still-lifes of 16th-century painters such as Frans Snyders, but one of my favorite depictions comes along much later: Asparagus Island, painted in 1860 by William Holman Hunt. The rocky outcrop off the coast of Cornwall, now owned by the National Trust, was once covered with a luxuriant carpet of wildlings, a reminder that the sprawl of Asparagus officinalis in the Old World roughly corresponds to that of the Roman Empire. The Romans excelled at recognizing a good thing when they saw it: Asparagus is one of the few perennial vegetables, and a modest bed of it in a sunny spot can thrive for 15 or 20 years.

"Asparagus Island, Kynance, Cornwall" (photo courtesy Christie's, London)

Green asparagus—today, the type most common in the United States—has spears that range from pencil-thin to thick. The difference in circumference is due not to the relative maturity of the spears but a combination of factors, including the relative age of the plants from which they were harvested (the thinner the spear, the younger the plant), variety, and sex. Female plants produce fewer, larger spears; males give a much higher yield of medium to small spears.

I tend to seek out asparagus that’s on the plump side because of its succulent, almost meaty, texture. I also find it easier to cook. Skinny asparagus may look elegant on the plate, but, as far as I’m concerned, it’s in the same category as angel-hair pasta: Both overcook in about a millisecond, and you are left with mush.

All that aside, go for whatever is the freshest, because asparagus doesn’t keep well. Look for firm, tightly closed tips, with a beguiling lavender blush, scales (or leaves, botanically speaking) that lie flat against glossy stalks, and woody ends that are freshly cut and moist.

My basic cooking method is as follows. It couldn’t be simpler.

Rinse the asparagus well to remove any sand, snap off the woody ends, and peel the lower half of each stalk. In a large skillet, lay the asparagus lengthwise in about an inch or so of salted water. Bring the water to a gentle boil and cook the asparagus until it is just barely tender; the tip of a knife inserted in a spear should meet a very slight resistance. Thin spears will probably be done in about 5 minutes; leave more robust spears in for at least another 5 minutes, testing them with a knife to gauge their doneness. Drain the asparagus on a clean kitchen towel. Once you’ve cooked asparagus this way, you can serve them hot, you can serve them cold, you can go in any number of directions.

The Season’s First Asparagus

Serves 2

This is all you need for a “Spring is Truly Here” supper. Make a generous amount of garlic toast, or, what the hell, cheese toasts with grated Gruyère. Cook about 1½ pounds of asparagus using the method above and melt some good sweet butter for dipping. In another pan, cook a thin slab of aged country ham until it’s crisp. (I have a cache of Benton’s finest in the freezer, but Edwards is good, too.) Put everything on the table at once and eat your fill.

Asparagus Mimosa

Serves 4

This is a wonderful way to begin a dinner party. The asparagus is delicious warm or at room temperature, and the sieved hard-boiled egg is more than a pretty topping: As it absorbs the vinaigrette, it fluffs up like the yellow mimosa blossoms that punctuate winter in Provence. The richness of the egg also gentles the vinaigrette and gives it body.

Cook about 1½ pounds asparagus as above. Cut two hard-boiled eggs in half, then press them through a sieve into a small bowl. Whisk together about 2 tablespoons white-wine vinegar, 1 tablespoon minced shallot, and a dab of smooth Dijon mustard, if so inclined (a little minced fresh tarragon would be nice, too). Add coarse salt and freshly ground black pepper to taste. Whisk in ⅓ cup extra-virgin olive oil—choose a mild one, rather than one that bellows “Tuscany!” Toss the asparagus in a small amount of the vinaigrette, and reserve the rest. Parcel out the asparagus among 4 plates, spoon the rest of the vinaigrette over it, and sprinkle with egg. Et voilà!

Asparagus Lasagne

Adapted from Gourmet

Serves 8

This last treatment is the genius child of Gourmet‘s former executive food editor Zanne Stewart, who wrote a wonderful, very personal column called “Forbidden Pleasures” for the magazine in the early ’90s. The first order of business is to roast the asparagus, a technique introduced to us by Johanne Killeen and George Germon, of Al Forno restaurant, in Providence, Rhode Island. During roasting, the natural sugars caramelize, coaxing out an ever-so-slight bitterness and overlaying the purity of the vegetable with a deeper, more complex flavor.

There are two more keys to greatness here. One is the easy-to-make, deceptively light sauce, and the other is a supermarket stand-by: no-boil lasagne sheets, the next best thing to tender homemade pasta. I tend to use Barilla because there’s no need to soak the sheets in water before using, but I imagine any brand will do.

4 pounds asparagus, trimmed and peeled

3 tablespoons extra-virgin olive oil

Coarse salt

½ stick unsalted butter

¼ cup all-purpose flour

1½ cups low-sodium chicken or vegetable broth

½ cup water

A 7-ounce log mild fresh goat cheese, softened to room temperature and crumbled

About 1 teaspoon fresh lemon zest

About 1½ cups grated Parmigiano-Reggiano or Gruyère, plus a handful for topping

1 box no-boil lasagne sheets (9 ounces)

1 cup cold heavy cream

1. Preheat the oven to 500ºF. Cut off the tips of the asparagus spears and set them aside. In a large bowl (work in batches if necessary), toss the asparagus spears with the olive oil, and spread them on 2 rimmed baking sheets. Roast them 5 to 10 minutes (depending on thickness), stirring them around in the pans, halfway through, until they are crisp-tender. Season the roasted asparagus with salt, and, when cool enough to deal with, cut the spears into fork-friendly lengths, about ½ inch or so.

2. Melt the butter in a medium pot, add the flour, and cook over moderately low heat, whisking, about 3 minutes. Whisk in the broth and water and simmer 5 minutes. Whisk in the goat cheese and lemon zest and season with salt to taste; whisk the sauce until it is silky smooth.

3. Skim-coat the bottom of a buttered 9- by 13-inch baking dish with a little sauce, then make layers of pasta sheets, sauce, roasted asparagus, and Parmigiano, ending with a layer of pasta. Scatter the uncooked asparagus tips on top. In a bowl beat the cream with a pinch of salt until it holds soft peaks, and spread it over the asparagus tips. Scatter that handful of Parm over the whipped cream and bake the lasagne on the middle rack of the oven about 30 minutes, or until it’s bubbling around the edges and golden on top. Let it stand 10 minutes to collect itself, then cut into slices and serve.

I’ve made this with great success at Easter, when neither lamb nor ham has appealed. It would also be lovely for Mother’s Day. My mother, who let me run wild in the garden, round and round a venerable asparagus bed, would have adored it.