SMOTHERED LETTUCE

I call New York City home, but I’m not from here. I grew up south of the Mason-Dixon, which is why I treasure the fact that local lettuces are available at the Greenmarket for most of the summer. Long after what I consider an early crop has disappeared, a variety like French Crisp, from grower Keith Stewart in the Hudson Valley, is still coming up in these parts, looking as fresh as the day is long. It even hung on through last week’s hot spell, which I think intensified its sweet, minerally flavor.

Great lettuce in a salad can’t be beat, but I want something more. Something richer and more substantial, yet still uncomplicated and fresh tasting. I want smothered lettuce—that is, lettuce slicked with a hot bacony dressing. It is sublime.

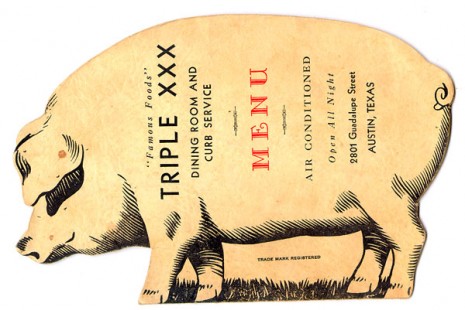

My parents introduced me to the dish as a child at the Nu-Wray Inn, a comfortable old country hotel high in the mountains of western North Carolina. It followed a typically mild lecture on the virtues of trying new foods, and one bite was enough to reel me in hook, line, and sinker. I suppose this was a life-defining event: I still presume the unfamiliar to be delicious until proven otherwise.

The concept of smothered (a.k.a. wilted or killed) lettuce is ancient; in the first century A.D., the Romans doused both raw and cooked lettuce with hot oil and vinegar. In its Appalachian form, it consists of nothing more than bacon drippings, the leaves of a thin-leafed lettuce variety like Black-Seeded Simpson, and chopped green onions, with their lanky-as-an-adolescent leaves. Generally speaking, one cook’s green onion is another cook’s scallion, but what I think of as green onions are a little more robust-looking than scallions. If you’re not sure what I’m talking about, check out the cover art on Booker T. & the M.G.’s first album. I learned how to snap my fingers to the title cut.

As you might imagine, the hot dressing lends itself to embellishment. The Nu-Wray’s recipe booklet advises adding a teaspoon of sugar and salt to taste to the lettuce and onion. “Pour over 2 tablespoons vinegar,” it then directs. “Fry five slices of cured country bacon crisply, and place strips upon lettuce. Pour hot bacon grease over all. Serve immediately.”

When my mother made smothered lettuce at home, she always used a bit more sugar, and disdained the cream that more mainstream cookbooks called for. Instead of green onions, she often used the green tops of the shallots that grew out back; I don’t recall that she ever paid any attention to the small, white-skinned bulbs.

Today, I find myself taking another tack entirely, reaching for pancetta instead of bacon, and searching Marcella Hazan’s Essentials of Classic Italian Cooking for a half-remembered recipe. Ah, here we go: “Smothered Boston Lettuce with Pancetta.” Hazan cooks the onion, along with the pancetta, in oil until it is deep golden, then adds the lettuce, letting the thick leaves simmer in their own juices. The treatment is really more akin to that of smothered steak, where braising tenderizes a tough cut of meat.

The thinner leaves of my lettuce won’t stand up to slow simmering, but I love the idea of wilting the greens on the stovetop to coax out even more succulence. Smothered lettuce is delicious with pork chops, sausages, or seared scallops. But don’t be afraid to serve with nothing more than a large spoonful of soup (pinto) beans and cornbread. Or focaccia.

Smothered Lettuce with Pancetta

Serves 4

You could use almost any lettuce here except iceberg; just adjust your cooking time depending on how thick the leaves are. Escarole or dandelion greens, with their more assertive flavor, would be delicious, too.

Mild extra-virgin olive oil

About ½ cup coarsely chopped pancetta, or enough to make you happy

A handful of thinly sliced spring onions or scallions (including the green parts)

About 1½ pounds lettuce (see above note), washed well, dried, and torn into manageable pieces

Salt and freshly ground black pepper

Cider or red-wine vinegar

1. Put a generous glug of oil in a large skillet and heat it over moderately high heat until shimmery. Add the pancetta and cook, stirring occasionally, until it crisps up and turns golden. Drain the pancetta on paper towels, and, in the fat that’s left in the skillet, cook the onions or scallions until they soften but still have some spunk.

2. Add the lettuce to the skillet, and don’t worry if it won’t all fit; once it begins to wilt, you’ll have room for what’s left. Add a sprinkling of salt and cook the lettuce, tossing it with tongs so that the leaves are all lightly coated with the hot fat and they begin to wilt yet still retain some crunch.

3. Transfer the smothered lettuce to a serving bowl and drizzle with the tiniest amount of vinegar to brighten. Scatter with pancetta and taste before seasoning with salt and pepper. Eat at once.

Posted: July 27th, 2011 under cookbooks, people + places, recipes, summer, Union Square Greenmarket.

Comments: 4