BARBECUE IN THE BLUE RIDGE

Heading south on Interstate 81, I follow what was once the Wilderness Road through the Shenandoah Valley. To the west is the crest line of the Allegheny Mountains and to the east, that of the Blue Ridge. It’s a nice drive, with picturesque views of pastureland and Constable skies, but the truck traffic is wearing. I’m ready to call it a day by the time I reach my exit, number 137.

West Main Street, Salem, Virginia. This stretch, lined with fast-food franchises and shopping malls, could almost be anywhere. Except for the surrounding high ridge of peaks—Poor Mountain, Twelve O’Clock Knob, and Fort Lewis Mountain are all as individualistic as longtime friends—you won’t find any real signs of personality until you get closer to the center of town, which is quiet, very sure of itself, and home to what is basically my second family. Every time I visit, I’m relieved to see that Miss Mona’s School of Dance—where generations of little girls have learned how to point their toes, pull up their knees, and perform precise piqué turns and buoyant pas de chat—is still hanging in there.

Sitting at a red light, I see McDonald’s on the left and Pizza Hut on the right. Burger King and Rancho de Viejo are just up the road, and I hear some citizens are lobbying for a Chick-fil-A. But the beckoning aroma that rolls through my open car window is all wrong, and on a couple of different levels, too. What I smell is real food. Slow food. What I smell is barbecue.

The source, a cheery red-and-white street rig, is stationed in a parking lot right across the way. I shoot past a far-too-bossy SUV and three pickup trucks to the next light, make a U-turn, and in no time find myself stepping out of the car into a billow of blue smoke.

Generally speaking, Virginia is not what you would call a barbecue destination, unlike neighboring North Carolina, Tennessee, and Kentucky. In those three states, the art and craft of smoking whole hogs or large slabs of pork over live fire gave rise to splendid, distinctive traditions. In Virginia, although you will find restaurants that serve barbecue—Memphis-style, Carolina-style, and what I call Crock-Pot style—this method of cooking never quite made the leap from social activity (often political fund-raisers or church suppers) to the commercial pit-barbecue roadside stands that are a dime a dozen to the south and west.

Now that Dennis and Jackie Norwood, of Rocky Mount, North Carolina, have taken to slipping across the border and infiltrating Salem with their custom-built smoker-on-wheels every week—they drive about 230 miles from their home Thursday mornings and stay through Sunday evenings—this situation could change.

In all honesty, “infiltrate” is not a word the Norwoods would use. They see themselves as missionaries. Barbecue missionaries enlightening the hospitable yet slightly backward folks of southwestern Virginia.

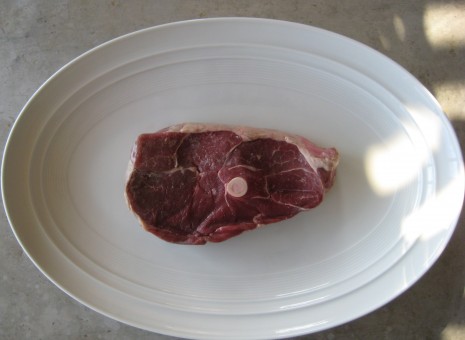

“Why Salem?” I ask. I’m halfway through my second sandwich. Like the first, it is rich, smoky, and laced with a homemade vinegar-based sauce handed down by Dennis’s grandfather. The coleslaw piled on top of the pork provides coolness and crunch. “Our daughter Janet lives in Salem,” Jackie explains. “Every time she comes home, barbecue is the first thing she wants to eat.” Well, that makes sense. Rocky Mount is a big barbecue town; just in case you find yourself in the neighborhood, it’s hosting the fourth annual Eastern Carolina Barbecue Throw Down this coming weekend, October 7 and 8*.

Jackie, recently retired from the daycare business, had always enjoyed making barbecue for special occasions, and when Dennis got laid off from an elevator-cable company, the couple decided to turn a hobby into a new line of work. “Rocky Mount is right in the back of Raleigh,” says Jackie. “We’ve got all the ingredients at our fingertips.” They started out at their church, and were an instant success. “Our barbecue is just like The Word,” continues Jackie. “We want to spread it abroad.”

The Norwoods’ daughter helped them get the necessary permits for bringing To God Be The Glory barbecue to Salem, and last year’s debut was at a concert in the park. A smash hit, they soon became a regular fixture on West Main, where you can buy ‘cue by the sandwich or pint. Saturdays only, there’s a dinner special of two meaty riblets, two corn sticks, slaw, and a drink for nine bucks. Dennis says he goes through 36 pork shoulders in four days, but I’ll bet it’s more if there’s a home game at the nearby football stadium. The Salem High School Spartans, who are having a good season, hope to make the playoffs.

When the wind is right, you’ll see any number of people in the packed stands sit up straight and work the scent like bird dogs. “Oh, they’re here!” someone exclaims. Fans look at one another, then gauge the action on the field. Then they get up and go.

* Which also happens to be Yom Kippur. When I mentioned this to Marcie Cohen Ferris, assistant professor of American Studies at UNC Chapel Hill and author of the masterful Matzoh Ball Gumbo: Culinary Tales of the Jewish South, she responded in characteristic, shoot-from-the-hip fashion. “Oh, no,” she said. “Sounds like two of the holiest days of the year are about to collide. Everybody take cover!”

Posted: October 5th, 2011 under autumn, favorite books, food, people + places.

Comments: 1