BONNIE’S BACK!

Jeremiah’s Vanishing New York, a blog by Jeremiah Moss, is a must-read for a certain kind of New Yorker. The writing is fine and knowledgeable, and the losses and injustices chronicled there in this Age of the Greedy Landlord are the sort of thing one chews over at three o’clock in the morning, when righteous indignation or, on occasion, impotent fury, is easier than sleep.

Last November, Moss had dire news for cookbook lovers everywhere: Bonnie Slotnick, a dealer in out-of-print and antiquarian cookbooks, was being forced out of the Greenwich Village shop she’d inhabited for 15 years. Bonnie isn’t what you might call a social media person, so she asked Moss to run an announcement she’d prepared for her customers.

“I’m still here!” she wrote. “But my landlord has refused to renew the lease on my shop. I’m looking for a small storefront in the East Village … but would also be open to other (marginally affordable) neighborhoods. It’s also possible that if I found the right person, I would consider sharing space—with another bookseller, an antiques dealer, a kitchenware shop. Maybe you’d be interested, or know someone who might? Rest assured that I will find a space, you will find your way there, and I will make it as cozy and welcoming as the old shop.”

The combination of resoluteness, good cheer, and an openness to opportunity is a powerful one. Bonnie’s circumstances came to the attention of sister and brother Margo and Garth Johnston, who moved with alacrity, offering her the ground-floor commercial space of their family home, an 1830s brownstone on East 2nd Street. “These wonderful people read of my plight and reached out to me,” Bonnie wrote in another announcement for Moss, “because in their eyes, a bookstore is the ideal tenant. Their late mother, Eden Ross Lipson, was the longtime children’s book editor at the New York Times Book Review, and it’s a book-loving family. It’s also a family that prizes the history and traditions of their neighborhood and appreciates the plight of the small-business owner.”

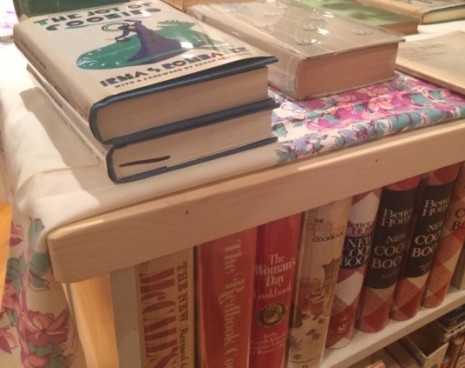

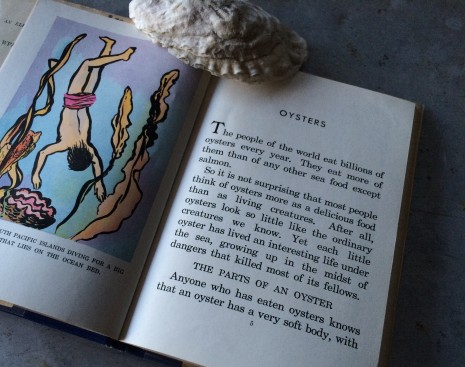

Although Bonnie specializes in cookbooks of the early to mid-1900s, her inventory stretches back to the mid-1800s. In addition to about 5,000 volumes, it includes ephemera and old kitchen implements, arranged like the sculptural objects they are. In other words, there is something for everyone, from serious collectors (she ships worldwide) to devotees of period salt-and-pepper shakers. Bonnie’s new store is three times the size of the old one, and she now has the room for book parties, readings, and a dedicated children’s corner, already furnished with the small, sturdy table and chairs Margo and Garth Johnston had when they were young. Bonnie gently fingered a faded duck decal on one of the chairs. “I need to get the story behind this,” she said.

When I stopped by the just-opened shop late last week, Bonnie and Margo were admiring the salvaged shelves that had been neatly jigsawed, as Bonnie put it, into every imaginable space. “I’m still trying to figure out what to do with the middle of the room,” she explained. “I’ve never had to think about that before!” For now, coins on the floor, scattered by one well-wisher, “for luck,” take pride of place.

The aromas of new paint and sawdust mingled invitingly with those of old books and freshly pressed vintage table linens, another one of Bonnie’s interests. She organized a drawer of aprons here, a stack of books there. The store’s location may be new, but its richly textured history is ongoing. Chinese-cooking authority Grace Young had come by to organize the Asian books, I heard. Bonnie’s contractor decided the fireplace needed a mantel, and just like that, she had one to showcase some absolute gems. Longtime friends, welcoming neighbors, and customers both old and new drifted in, all happy to be there. Somewhere, Eden Ross Lipson is smiling.

Bonnie Slotnick Cookbooks, 28 East 2nd Street (between Second Avenue and the Bowery), 212.989.8962; bonnieslotnickcookbooks.com.

Posted: March 3rd, 2015 under cookbooks, people + places.

Comments: none