RECIPE FOR HAPPINESS: CREAMLESS CREAMY CORN WITH FRESH CHIVES

“People have tried and they have tried, but sex is not better than sweet corn.” —Garrison Keillor

Sweet corn is one of America’s great icons of summer. Harvested when the ears are tightly jacketed in green leaves and the kernels are plump with milky-looking juice, it’s piled high at roadside farm stands, and odds are you’ll see skid marks on the pavement out front.

A number of connoisseurs in my neck of the woods flock to Country View, on the Main Road in Southold, New York (just past the North Fork Table & Inn). The place’s one-stop shopping appeals to anyone who just wants to get horizontal in a hammock or beach chair and not have to worry about supper. Plus, the corn is outstanding—sweet but not sugary, with tender, juicy well-formed kernels and pure corn flavor that comes through loud and clear.

One of the things I like about Country View is that you have to know to ask for the corn. It’s not heaped out front as a calling card, but kept on a shelf near the cash register, away from gimlet-eyed customers who, ignoring any hand-scrawled signs to the contrary, strip the husks to inspect the ears, then toss the rejects back on the pile. That behavior results in ruined, unsellable corn: Once the kernels are exposed to the air, they begin to dry out (thus toughen) and lose nutrients to boot.

Removing the self-serve aspect may seem insidery and a little off-putting, but the good folks behind the counter are simply doing their best to prevent corn carnage—and more power to ’em, for I’ve never gotten a less-than-stellar ear. The fact that the corn isn’t genetically modified—and is labeled as such—is another reason I happily give them my food dollars.

The way you can tell if plump, even kernels have filled out the whole cob, by the way, is to simply feel around the top of the ear through the husk. The shank (stem) end should look recently cut, the husks should be a vivid green and slightly moist, and the silk at the top should feel slightly tacky to the touch.

As to why some ears boast fat kernels from stem to stern and others don’t, it has to do with, well, what Garrison Keillor was talking about. The corn plant has both a male part (the tassel at the top of the plant) and a female part (the ear, which consists of cob, kernels that develop after pollination, and silks). Wind carries pollen from the tassel of one corn plant to the silks of another, and each of those silks is connected to a potential kernel of corn inside each ear. If pollen reaches a silk, it causes a corn kernel to grow; if a silk doesn’t receive pollen, its kernel remains small and undeveloped.

And that is why in this day and age of seedless watermelons and stringless green beans, we are still cleaning that glossy floss off ears of corn. If you are a waste-not-want-not sort of person, or have young children who would love a garden tea party (strawberry sandwiches are always a hit), you might want to make corn silk tea. In the words of my former colleague Kempy Minifie, it tastes like a summer day.

When you get your hands on really good sweet corn, it’s almost a criminal offense to overcook it. With ultrafresh ears, I simply chuck them in a pot of boiling water, wait until the water just returns to the boil, then turn off the heat and let the pot sit, covered, until the rest of supper is ready. Lately, it’s been so tender and good that I eat it without any embellishments at all—no salt, no butter, nothing.

But there are times when I want something more, something that will add a grace note to smoky, meaty ribs from a takeout joint or an old-fashioned chicken dinner, complete with snap beans and hot biscuits with blackberry butter.

The recipe below does the trick. Yes, you need a food processor, a fine-mesh sieve or strainer, a saucepan, and a sharp knife, but as the culinary mastermind Richard Olney (who would have been 87 yesterday) once wrote, simplicity can mean perfection or harmony in a dish rather than ease of preparation. In other words, it’s worth it.

Creamless Creamy Corn with Fresh Chives

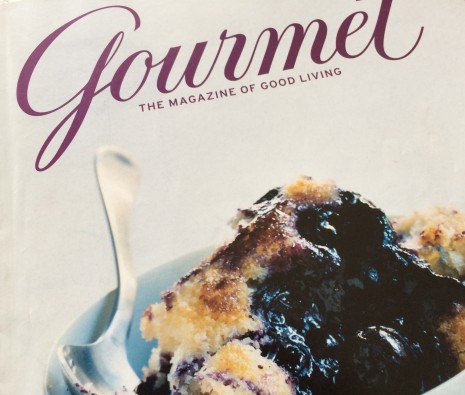

From The Gourmet Cookbook (Houghton Mifflin, 2004)

The creaminess in this dish comes from the milky juice in the corn itself. This is the essence of fresh corn; the recipe serves four, but you might not want to share. And if you don’t have fresh chives ready to hand, don’t sweat it—shreds of fresh basil are lovely, too.

4 ears corn, shucked

¼ teaspoon coarse salt

¾ teaspoon cornstarch

Pinch of sugar (optional)

2 tablespoons unsalted butter

¼ cup finely chopped onion

1/3 cup water

Freshly ground black pepper

2 tablespoons finely chopped fresh chives

1. Working with 1 ear at a time, lay the cob on its side on a cutting board and cut off the kernels with a large knife, rotating the cob as you go. Transfer the kernels to a bowl, then hold the cob upright in the bowl and scrape with the knife to extract the “milk.”

2. Transfer 2 cups of the corn kernels to a food processor and purée 2 minutes, scraping down the sides of the processor bowl once or twice. Force the purée through a fine-mesh sieve into a bowl; discard the solids. Stir in salt, cornstarch, and sugar if using.

3. Melt the butter in a 2- to 3-quart saucepan over moderately low heat. Add the onion and cook, stirring occasionally, until softened, about 3 minutes. Add the remaining corn kernels, corn milk, and water. Cover and simmer briskly, stirring occasionally, until the corn is crisp-tender, 4 to 5 minutes.

4. Stir the corn purée, then stir into the corn kernels. Bring to a boil, stirring, then reduce heat and simmer, stirring frequently, 2 minutes. (If desired, thin with additional water.) Season with pepper and stir in chives.

Posted: August 5th, 2015 under cookbooks, Gourmet magazine, people + places, Recipe for Happiness, recipes, summer, vegetarian.

Comments: none