SCRATCH SUPPER: WARM LENTIL SALAD WITH KIELBASA

Scratching together a nourishing, delicious meal at the end of the day is one of life’s greatest challenges. Two staples that make that easier in our household are lentils and sausage, especially the smoked Polish variety called kielbasa.

Lentils are one of the greatest pleasures of the legume world. They cook quickly (and unlike most dried beans, there’s no soaking beforehand), adapt to any number of flavor palettes, and slide from homey to haute with ease. I suppose you could say they’ve been around the block and know a thing or two: After all, they were there in the beginning—er, Beginning—as the pottage for which Esau gave up his birthright in Genesis 25:34. I, for one, have great sympathy for him. Who wouldn’t be tempted by a bowlful of something so simultaneously earthy and rich-tasting?

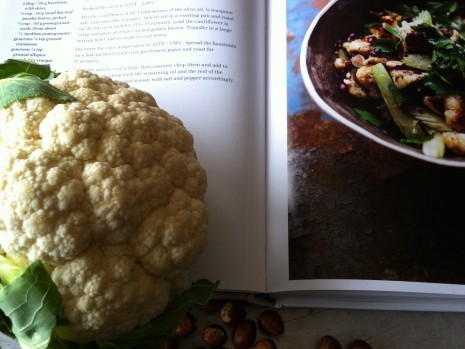

The pretty green lentils you see above are the renowned French ones called lentilles du Puy. Named for the town of Le Puy, a tile-roofed town in the mountains of Haute-Loire, they have their own appellation d’origine contrôlée. Don’t presume that the tiny “French green lentils” in the bulk-bin section of the supermarket are true lentilles du Puy; look for that A.O.C. seal on the package when buying (Saborat is the brand I see most often). Yep, I know they’re more expensive than the other lentils on the shelf, but they’re worth it. Their characteristic flavor—peppery and minerally yet delicate—comes from the rich volcanic soil and dry, sunny climate in which they’re grown. And because they contain less starch than other varieties, they exhibit a lovely firm-tender texture when cooked. In fact, if your opinion of lentils was formed by one too many mushy stews in bad vegetarian restaurants, then these will be a revelation.

The lentils of Puy make a great bed for slices of duck breast, duck leg confit, or a piece of seared fish. They are lovely scooped into the hollows of a baked winter squash or sweet potato, or tossed with small pasta shells and a crumbly, mild fresh goat cheese.

What I do most often, though, is serve them in a bistro-style warm salad with kielbasa. If I’m fortunate, my fridge may hold one from Eagle Provisions, in Brooklyn, “manufacturers of the world’s finest kielbasy,” but more often than not, I make do with one from the supermarket, or skip the sausage entirely and fry up pancetta or lardons—thick-cut strips of bacon sliced into matchsticks and cooked until crisp—instead.

Warm Lentil Salad with Kielbasa

Adapted from Gourmet magazine

Serves 4

The mix of aromatic vegetables in this salad is really satisfying, but it varies depending on my time and inclination—as well as the contents of the refrigerator. It’s perfectly delicious with nothing more than onion and garlic, or carrot and garlic. All you need alongside is some good bread and butter, but a green salad is always welcome as well.

2 cups French green lentils (lentilles du Puy), picked over and rinsed

6 cups water

1 bay leaf

A couple of sprigs of fresh thyme or, if you can find it, winter savory

Coarse salt and freshly ground pepper

½ cup plus 2 tablespoons extra-virgin olive oil, divided

1 cup finely chopped onion

1 cup diced carrot

1 cup diced fennel or celery

1 tablespoon finely chopped garlic

¼ cup red-wine or Sherry vinegar

1 tablespoon Dijon mustard

1 smoked kielbasa sausage, cut crosswise into ¼-inch slices

Fresh flat-leaf parsley or celery leaves, chopped, for serving (optional)

1. Bring the lentils, water, bay leaf, and thyme sprigs to a boil in a 3-quart pot. Reduce the heat and simmer the lentils, covered, until they are almost tender, about 15 minutes. Add ½ teaspoon salt and keep simmering until tender but still firm, about another 5 minutes. Meanwhile, heat 2 tablespoons oil in a large skillet over medium-low heat. Add the onion, carrot, fennel, and garlic and cook, stirring every so often, until the vegetables are just softened and smell delicious, 8 to 10 minutes.

2. While the lentils and aromatics are both working, make the vinaigrette: Whisk together the vinegar and mustard in a small bowl and then whisk in the remaining ½ cup oil. Season to taste with salt and pepper.

3. Drain the lentils in a colander, discarding the herbs. Return the lentils to the pot and stir in the vegetables and vinaigrette. Cook over low heat a few minutes until nicely hottened up; remove from the heat and cover to keep warm. Wipe out the skillet and brown the kielbasa on both sides. Stir into the lentils, along with the parsley, and serve.

Posted: February 20th, 2013 under Gourmet magazine, recipes, scratch supper, winter.

Comments: none