Coleslaw gives coolness and snap to almost any summer meal. It transcends the categories of salad, side, relish, sandwich topping with confidence and ease. And as with other age-old dishes, variations abound. Here are three of my favorites.

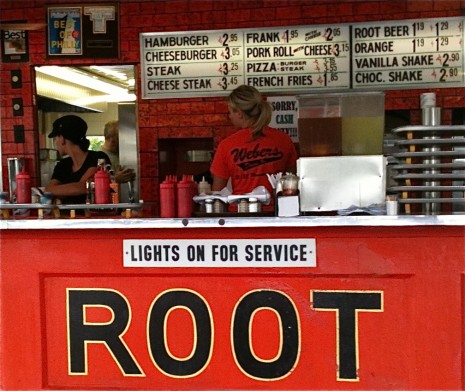

Craig Claiborne’s coleslaw, below, is an homage to the straightforward type you’ll find in Goldsboro, North Carolina, a city known for the style of barbecue you get in the eastern part of the state. For the uninitiated, that’s whole hog meat that’s been chopped fine and seasoned with a thin, non-tomatoey vinegar-based sauce. Order a barbecue sandwich and on top or alongside comes a creamy coleslaw to offset the tang of the sauce. It is one of the world’s great flavor combinations, and right now, I’m intensely regretting the circumstances that are keeping me here in New York, and not packing for the Southern Foodways Alliance Carolina Field Trip later this week.

At least my shipment of Duke’s mayonnaise arrived, and a good thing, too; we were coming to the end of our last jar. If you grew up with Hellmann’s, you may presume that because Duke’s is a southern brand (it was created by Eugenia Duke in 1917, in Greensboro, South Carolina), it must be cloying. Not no, but hell, no. Simultaneously rich and fresh tasting, it’s the only major brand of mayo that doesn’t contain any sugar.

Since the 1960s, however, it has contained soybean oil—today, a red flag to anyone trying to keep GMOs out of their food. According to the customer service folks at Duke’s (owned by C.F. Sauer Company since 1929), the original oil used was probably cottonseed, so I can’t get my nose too much out of joint here. Still, wouldn’t it be great if companies like Sauer agitated for increased availability of non-GMO oil?

Goldsboro Coleslaw

Adapted from Craig Claiborne’s Southern Cooking (Times Books, 1987)

Serves about 6

The last two ingredients in this recipe—a tiny amount of sugar and cayenne or smoked paprika—are our usual embellishments, but my husband and I will often include grated carrot as well. If you’re serving the slaw with seafood—boiled shrimp or crab cakes, say, or lobster rolls—stir in a smidgen of fresh lemon zest and a drizzle of lemon juice. For a tangier coleslaw, replace some of the mayo with a dollop of sour cream. When tinkering, don’t forget to taste as you go. You can always add more mayo, salt, or cayenne, for instance, but you can’t remove them once they’ve joined the party.

1 small cabbage (about 1½ pounds)

1½ cups mayonnaise

1 cup finely chopped onion

Coarse salt and freshly ground pepper

A scant ½ teaspoon sugar (optional)

A pinch of cayenne or Spanish smoked paprika

1. Remove the core of the cabbage and the tough or blemished outer leaves. Cut the head in half and shred fine. There should be 6 cups. Coarsely chop the shreds and put them into a mixing bowl.

2. Add the mayonnaise, onion, salt, and pepper and toss to blend well. Let the slaw sit about 30 minutes so the cabbage wilts a bit and the flavors have a chance to mingle.

Now, I am perfectly aware of the fact that I could make my own mayonnaise. But after almost 20 years at Gourmet—where we all had to be mindful of food safety issues—uncooked eggs, even organic ones, are risky, and I just don’t want to be the enabler of a Salmonella outbreak. Instead, when I have a yearning for my grandmother’s—or great-grandmother’s—coleslaw and 15 minutes to spare, I make boiled dressing, which isn’t boiled at all, but gently cooked until it reaches a satin-smooth, custardy consistency.

The recipe below may sound rich as all get out, but it is remarkably pure and clean in flavor. It makes a great egg-safe alternative to homemade mayo in coleslaw, potato salad, egg salad, or deviled eggs, and will take asparagus or green beans to the moon and back.

Boiled Dressing for Old-Fashioned Coleslaw

Adapted from Gourmet

Makes 1½ cups

3 large egg yolks

1 tablespoon all-purpose flour

1 tablespoon sugar

1 teaspoon coarse salt

1 teaspoon dry mustard

1¼ cups whole milk

1 tablespoon cider vinegar

3 tablespoons unsalted butter, cut into small pieces

1. Whisk together the egg yolks, flour, sugar, salt, and dry mustard in a 1-quart heavy-bottomed saucepan. Then gradually whisk in the milk and vinegar.

2. Cook gently (do not let boil) over moderately low heat, stirring constantly with a wooden spoon, until the mixture is thickened (you’ll feel the change in your wrist) and just registers 160ºF on an instant-read thermometer.

3. Immediately pour through a fine sieve into a bowl, then stir in the butter until melted. Put the bowl in a larger bowl of ice and cold water and let cool, stirring occasionally. Cover the surface with wax paper before refrigerating in an airtight container. Boiled dressing keeps at least a week, but you will probably eat it up before then.

Even though my heart belongs to creamy coleslaws, there are times when I want something lighter and brighter. That’s where this slaw comes in. It isn’t as dressed as a classic slaw; instead it gets presence from toasted Asian sesame oil, the dark brown, roasty-toasty type that’s used as a condiment, not for cooking. This slaw also turns out to be extremely handy when you need to improvise an hors d’oeuvre (serve in endive or radicchio leaves) or a first course. Crisp slivers of kohlrabi or summer’s first turnips are among my swaps for the kale. Any leftovers are delicious for lunch the next day.

Coleslaw with Kale and Radishes

When I said “improvise” above, I wasn’t kidding. I put this together in about ten (desperate) minutes last week, and did I even think about measuring? No such luck.

About 1 pound of cabbage, cored and sliced thin

A few leaves of fresh, tender kale (I used lacinato)

A handful of radishes, trimmed

Coarse salt

Safflower oil, canola oil (preferably non-GMO), or very mild extra-virgin olive oil

Rice vinegar

Toasted Asian sesame oil

1. Put the cabbage in a bowl. If your kale is young and the stems and center ribs are tender, count your blessings and don’t bother to discard them. Simply stack the leaves, roll them up tightly, like a cigar, and cut them into very thin slices. Add them to the cabbage. Holding a box grater over the bowl, grate the radishes on the large holes directly into the slaw. Lightly season with salt and let sit about 15 minutes, while you tidy up for company.

2. Gently toss the slaw with a drizzle of safflower oil and some rice vinegar. Taste, then toss with a little of the toasted sesame oil. Taste again and adjust seasoning.